Projects

This is where I will be keeping up to date progress reports of my projects via photos and documents.

| Unmanned Systems | Space Exploration | Extracurricular |

|---|---|---|

| Anything remotely controlled, semi-autonomous, to fully autonomous robots (multirotors, helicopters, planes, planetary rovers, boats and submarines). | CubeSat: mechanical and electrical design, antenna design, space-segment-software design/implementation/testing/deployment/maintenance, wireless communication, thermal/vibrational/vacuum testing and reliability. | Software Dev (web/apps, games), internet of things, VR/AR, cloud geospatial analytics tools, big data, machine learning, blockchain, cryptocurrency, GPS. |

Drones

I am active in the DIY-UAS community on DIYDRONES and I’m always willing to provide advice/assistance as well as learn from others. I have practical experience in planning and executing aerial surveys (using UAV technology), acting as a navigator/pilot, writing approved Special Flight Operations Certificates, and developing UAV technology/platform solutions.

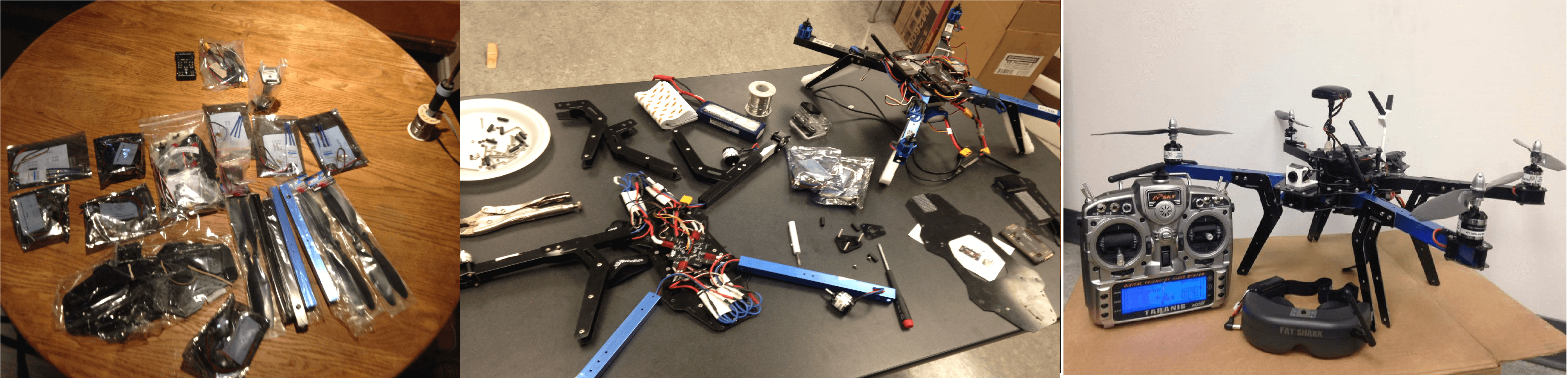

When I first purchased my drone, I received a large box of small intricate parts and limited instructions. I really have to thank the community for all the progress I made and problems I solved. From left to right, you can see the progression and integration of FPV goggles/camera, 3D printed parts, and my programmed controller.

When I first purchased my drone, I received a large box of small intricate parts and limited instructions. I really have to thank the community for all the progress I made and problems I solved. From left to right, you can see the progression and integration of FPV goggles/camera, 3D printed parts, and my programmed controller.

One of the final tests of my power-over-tether UAV project (Summer 2016)

CubeSats

I’ve also working on various nanosatellite (CubeSat) development projects at the Lassonde School of Engineering. The main one being the Canadian Satellite Design Challenge Team at York University. Our challenge is to design and build a 3U CubeSat from scratch using limited commercial off the shelf components by mostly designing it ourselves. The competition information can be found here. I also played an important role in the team working towards the QB-50 project.

From top left row to right: you can see the battery testing and validation process we went through for the QB50/CSDC satellite(s). We conducted vibration tests with clamps that will be used for securing the batteries to the spacecraft, cycle testing to determine the End-of-Life for the batteries, and vacuum testing (because space is a vacuum). The bottom row, shows our testing of the protection circuit using LabVIEW, testing of the solar panel’s peak-power, and we also vibration tested a Beagle Bone Black because we were thinking of using it for the OnBoard-Computer.

From top left row to right: you can see the battery testing and validation process we went through for the QB50/CSDC satellite(s). We conducted vibration tests with clamps that will be used for securing the batteries to the spacecraft, cycle testing to determine the End-of-Life for the batteries, and vacuum testing (because space is a vacuum). The bottom row, shows our testing of the protection circuit using LabVIEW, testing of the solar panel’s peak-power, and we also vibration tested a Beagle Bone Black because we were thinking of using it for the OnBoard-Computer.

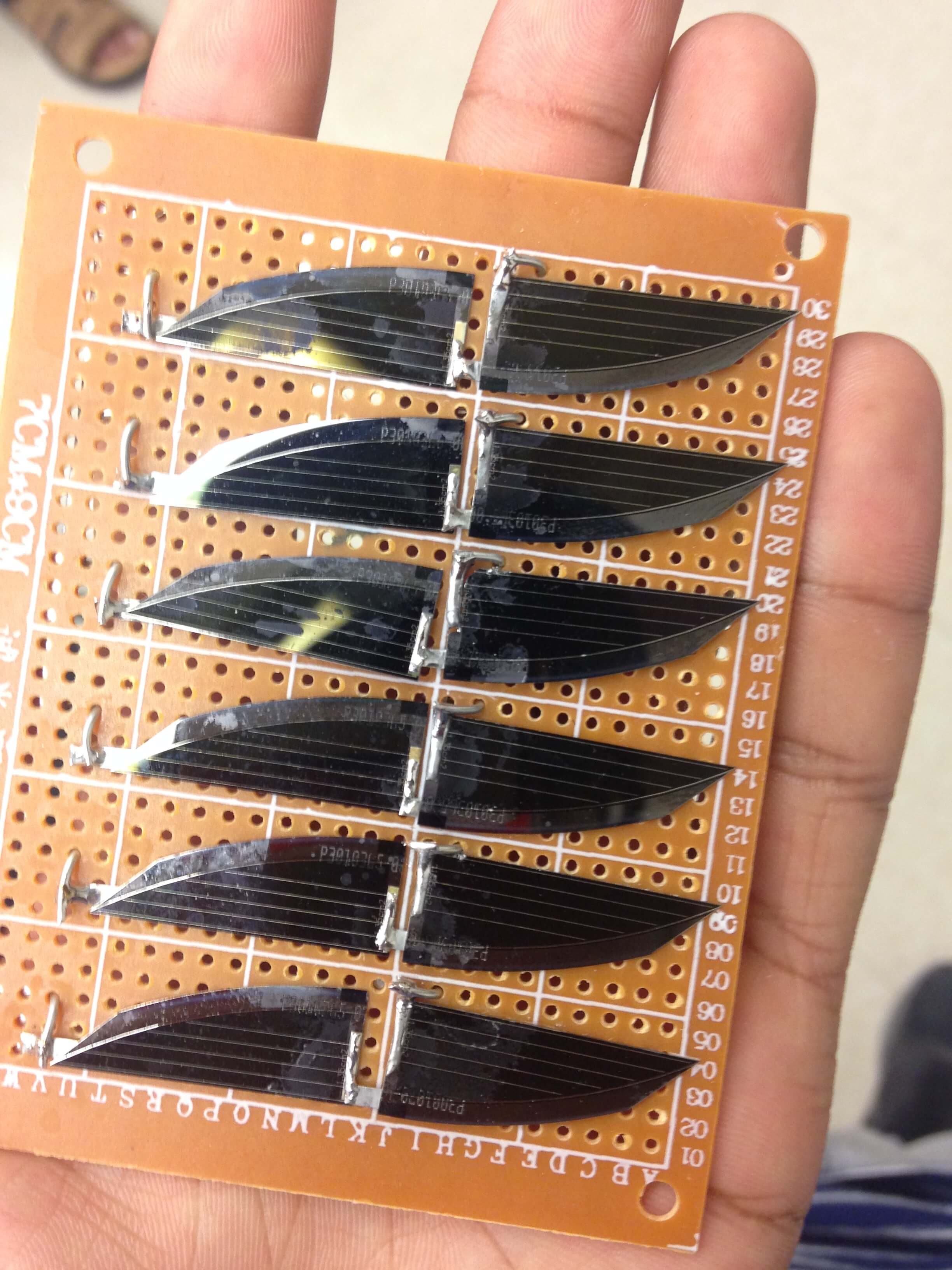

Here’s a glimpse of our proto-type solar array that our advisor helped us solder together.

Here’s a glimpse of our proto-type solar array that our advisor helped us solder together.

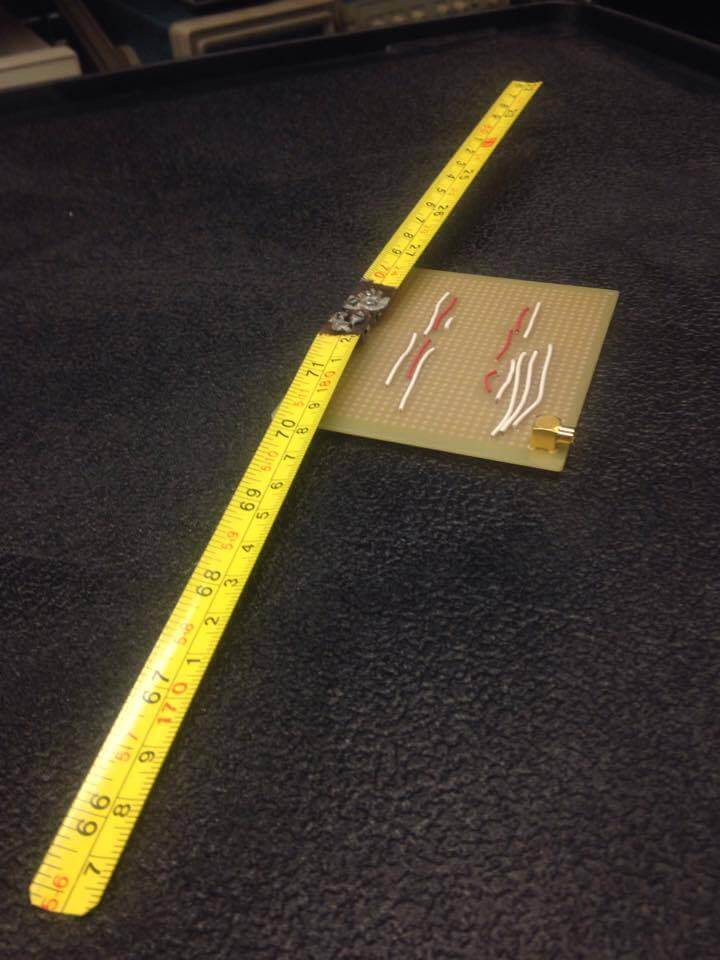

Here’s a glimpse of our proto-type antenna. Yes its two pieces of measuring tape slapped to a PCB, and yes it transmits radio frequencies. Trust me, I didn’t believe it myself.

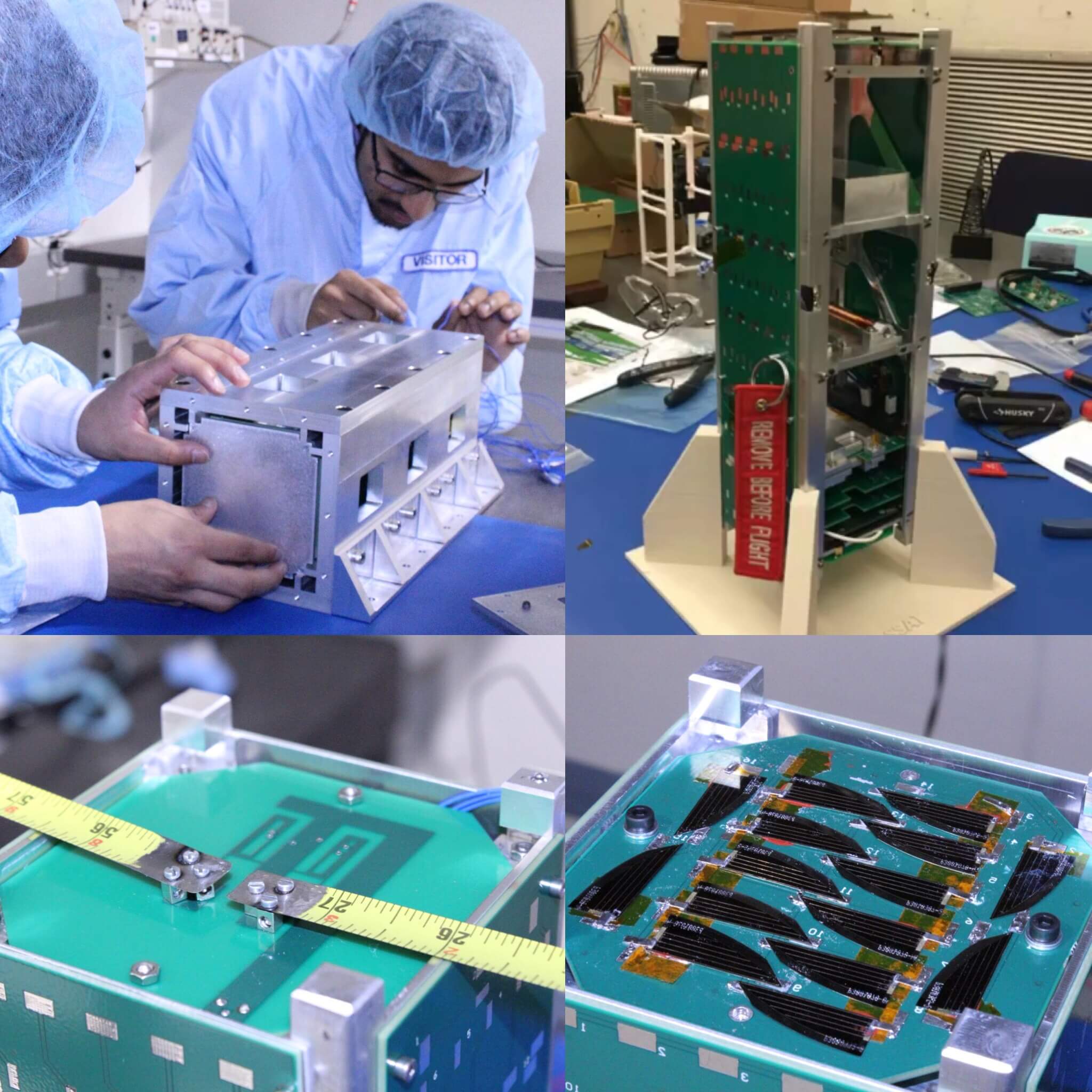

The final product offering for the CSDC-4 FDR, displaying P-POD (Poly-Picosatellite Orbital Deployer) integration plus our custom solar array and antenna design. We also got to tour the Canadian Space Agency’s David Florida Laboratory in Nepean, ON.

Please follow CSDC@YorkU via the links on my Contact Page > Organization to follow and support us on our journey!

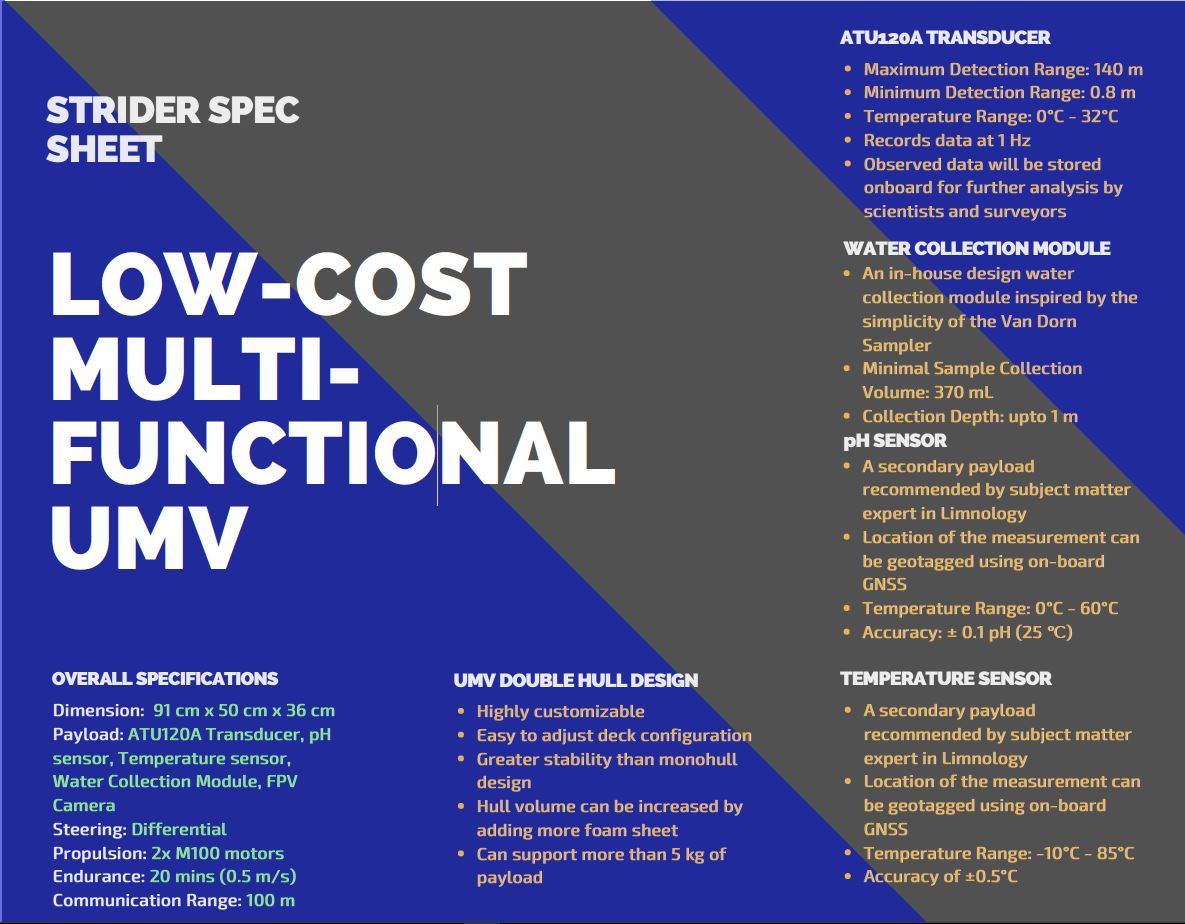

Unmanned Marine Vehicle (UMV)

For my final thesis/capstone engineering project, I teamed up with my close friends that were apart of the CubeSat team with me.

From left to right: Ekram Bhuiyan - Computer Engineering, myself, and Mohammed Kagalwala - Space Engineering.

From left to right: Ekram Bhuiyan - Computer Engineering, myself, and Mohammed Kagalwala - Space Engineering.

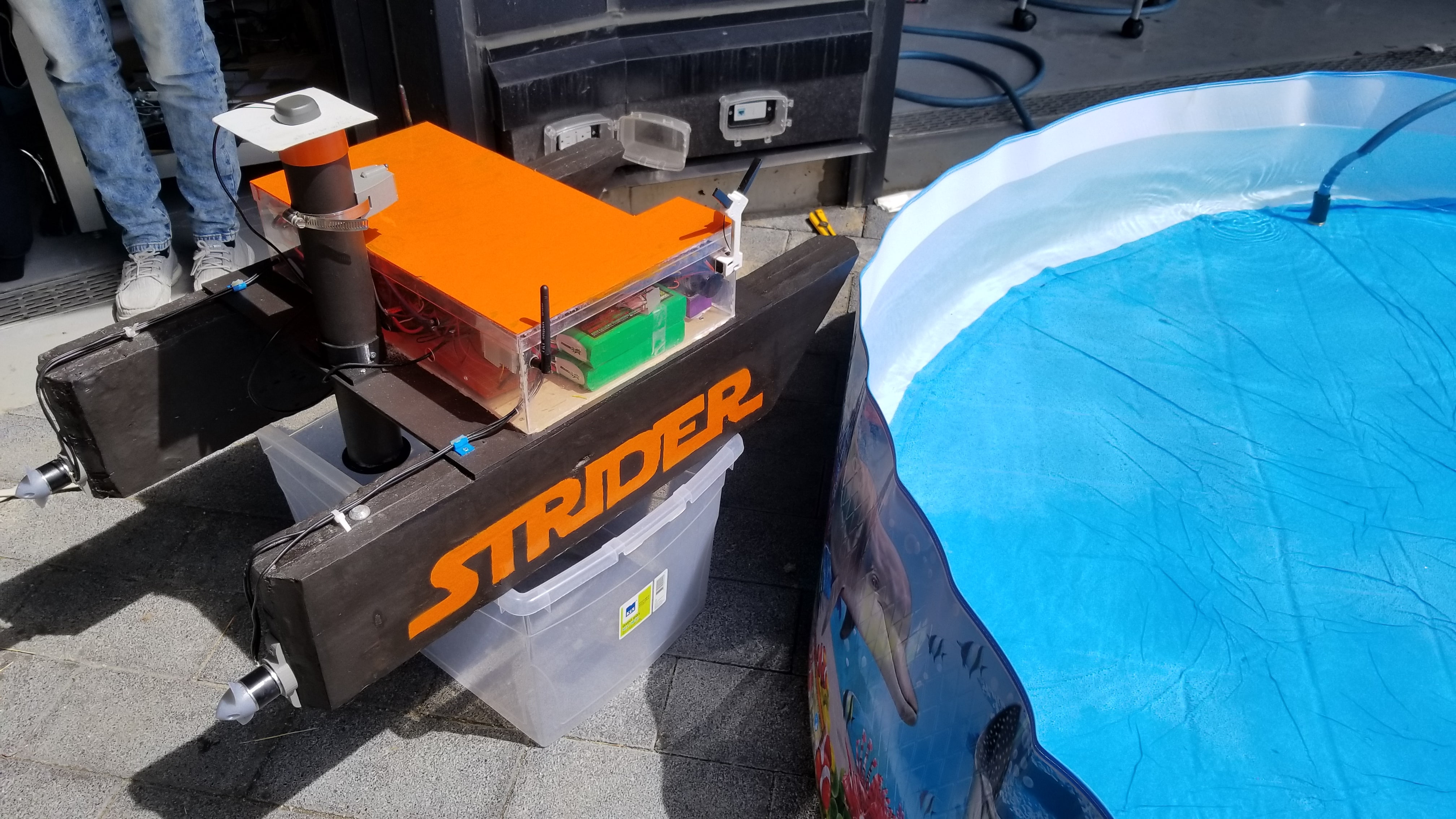

We started with an idea proposed by Prof. Costas Armenakis (who was my advisor for the UAV research projects) targeting the Hydrography course’s ability to incorporate practical labs. Upon further research, we saw a hole in the market for a low-cost UMV capable of completing remote surveying (either little RC boats or expensive survey-grade vehicles). This drove us to create a low-cost UMV, by integrating high-quality commercial off-the-shelf technology to deliver real-world data and practical training for students.

Why stop there? Speaking to one of our industry advisors, an experienced hydrographer, he suggested adding a camera system to allow for remote surveillance. Further reaching out to limnologists, who shared a great interest in our project, we integrated pH, temperature and water sampler payload. The sensors/systems offered great value for minimal cost. They were great complimentary payloads, as they benefited from the high accuracy positioning technique called Real-time Kinetic (RTK) GNSS (which I also integrated on UAV platforms). The high-accuracy positioning was critical to the hydrographic payload (i.e. transducer/echo sounder).

Using my experience from UAVs, I made the system capable of performing automatic surveying (i.e. waypoint navigation) through a Ground Control Software (GCS) interface, this made the hydrographical surveying process much more efficient. The GCS could also be used for monitoring mission-critical services like battery life, real-time location, GPS-lock status, inertial sensor readings, and changing system parameters such as failsafes. Nothing typically goes as planned so we had failsafes for low battery, loss of GCS/RC communication, operations outside geo-fenced regions, and more.